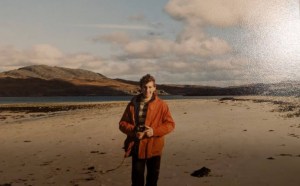

Back in November, Iain, Penny, and I got chatting about the Isle of Jura, in the Southern Hebrides. We quickly discovered that we all shared a great fondness for the place. Iain had visited the island in 1984 as part of a university field trip; Penny had visited many times, on her own and with the family, exploring and camping on the west coast; and I’d been a bunch of times too. For all of us, the ‘Jura wilderness experience’ was formative and impactful. We shared strong, lasting memories of wild coastlines, remote camps, caves, raised beaches, sea eagles, otters, wild goats, and red deer. It was time for a return visit.

Some quick facts about the Isle of Jura:

- It’s a big island (30 miles long) with a very small population (200 people).

- The west coast is divided into two by Loch Tarbet. The entire West Coast is uninhabited.

- There are 6000 deer, and the main employment is linked to shooting estates.

- It has a distillery, making Jura malt.

- The island’s earliest inhabitants were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, 9000 years ago.

- Jura has incredible coastal geomorphology. During the last glacial maximum in Britain (27,000 to 20,000 years ago), a large ice sheet covered Scotland, Ireland and northern England. The tremendous weight of ice depressed the land. Over time, the ice sheet receded, and by 11,500 years ago, it was gone. The disappearance of all that weight of the ice made the land bounce upwards, leading to a relative drop in sea level. This ‘isostatic rebound’ created an uplifted coastline with raised beaches and dry caves, arches and sea stacks, all well above the current sea level.

- At the northern end of Jura, between Jura and Scarba, lies the Gulf of Corryvreckan, home to the third-strongest tidal stream in the world. There is a very narrow tidal strait at the southern end of Jura, too, at Feolin.

- Somerled, the twelfth-century warlord and progenitor of the Clan Macdonald, won the Southern Hebrides from the Vikings. He built a defensive stronghold at Feolin.

- George Orwell wrote 1984 at Barnhill, a remote house, in the far north of the island.

- The island is renowned for its wild and rugged terrain; horrendous tussock grass and bogs; wild goats, adders, eagles and otters; ticks, midgies and horse flies; and impenetrable bracken and bramble!

Iain took on the organizing role, and a plan took shape. We’d visit in early December and attempt to trek the west coast of the island, north of Loch Tarbet, over four days. We decided upon the expedition aesthetic, as we called it, a set of principles that would shape our journey. For millennia, the island’s caves have provided shelter for itinerant hunters, exploring the island’s coastline for shellfish, hazelhuts and red deer. It seemed fitting then that our style of journeying would be stripped back, ascetic, and austere. A simple tarp, paracord, home-made firelighters, and wellies were among our kit. We’d use a tarp rather than a tent, seek shelter from the rain and wind in caves and use driftwood fires to keep us warm. I took the aesthetic a little further, bringing a woolly jumper and cotton (ventile) smock, and taking a bushcraft knife to make a walking stick, tent pegs, and a spear for hunting goats (just kidding!). Less fancy kit, more bushcrafty, more self-reliance! That was the rough plan anyway, although we would make use of some bothies too.

The weather forecast deteriorated badly in the days running up to our trek. Heavy rain and 50mph winds were forecast! There was some nervousness in the group, but I felt pretty confident. 29 years ago, I had done the same trek with my pal Jim. I remember bimbling along the coast, with lots of time to explore caves and take it all in. “It’ll not be that bad”, I reassured Penny and Iain. My confidence was misplaced.

We arrived at Craighouse, the main settlement on Jura, late afternoon on Saturday 3rd of December. We set up camp with our tarps in the grounds of Jura hotel, taking some time to practice the art of tarpology: getting the angles and peg placements just right to form a tent-shaped shelter with our 3×3 tarps. Then dinner and beer in the hotel.

The next morning, it was raining heavily. We quickly rearranged the tarp setup, suspending a ridgeline between two trees and erecting a diamond-fly-shelter for the three of us to cook under.

At 8:30 am, a taxi picked us up, and we drove north along the small single-track road along Jura’s east coast. We dropped Iain’s car off near Loch Tarbet, about halfway up the island, then continued north to the end of the road. From our drop off point, our first goal was to reach the end of the track, on the east coast, which took one to Barnhill and then the very last house, Kinuachdrachd. The first part of the journey was easy enough. We popped in to have a look at Barnhill. We peered through the windows at furniture and a decor that looked little changed since George Orwell’s stay in 1948. Penny and I nostalgically imagined what it smelt like inside: coal fires, wooden floorboards, wool rugs, old books, and a little damp and stale. George Orwell was suffering from Tuberculosis when he was here, and died shortly after leaving.

After some food by Kinuachdrachd, we headed into the wilds. The terrain from hereon would be difficult, with bog, heather and tussock grass. Finding and following deer and goat tracks was key, and better still, the tracks left by argo-cats, small eight-wheeled vehicles used by stalkers. Before long, we reached a high point in the north and looked out across the Gulf of Corryvrekken. Twice a day, the tidal stream rushes through the narrow strait between Jura and Scarba, creating standing waves, whirlpools and eddies. In places, the water spilt up from below, making the surface look black, smooth, slick and ominous. Apparently, George Orwell and his son nearly drowned in the Gulf, having ventured out there in a small boat.

Rounding the northern end of the Jura, we caught our first glimpse of the west coast. Two sets of coastline presented themselves: a lower rocky shoreline where the sea erodes the quartz, and a higher ‘fossil’ shoreline, with large cliffs and caves, formed thousands of years ago. It looked to me like a lost world, prehistoric, dangerous and inhospitable. A short-eared owl popped up from in front of us. Then we saw our first herd of wild goats. What an amazing place.

It was about 1 pm, and our next goal was to progress around Bagh Gleann nam Muc (meaning Bay of the Pigs). “About one thumb,” said Penny, “and then to Glen Garrisdale bothy, about another 4 and a half thumbs”. Throughout the journey, we became accustomed to Penny’s unique unit of measurement… thumbs, which, on a 1:50,000 scale map, was equivalent to a mile. Progress was concerningly slow. We weaved our way up and around crags, bogs and pools, looking for goat tracks where we could. It took 50 minutes to do a mile. This was going to take a while.

We cracked on, making slow progress, sometimes finding a flatish route by the sea and sometimes, impeded by cliffs, having to ascend up steep slopes to find a high route. Making a judgment about whether to go high or low was tricky. We couldn’t always tell from the map which way was best. If we went low, it was easier, but we risked getting stuck and having to backtrack. About an hour before dark, we reached such an impass. A cliff extended out to the sea, blocking our route. Our choices were to back-track, climb up the cliff or venture around the base of the cliff, over slippery rocks. The low route was best, I decided. We crept over the slimy rocks, reaching a point where we had to get over a pool, being swamped by waves. Choosing our moment, we leant across to a boulder and heaved ourselves up, then scrambled over a short step to safety. It was all a bit unpleasant.

By 4 pm, it was dark and raining. For a good while, we followed in Penny’s wake. Using her night vision, she efficiently found a good line, joining up deer and goat tracks to a bay about a thumb’s distance from the bothy. The coastline ahead looked complex. We didn’t want to risk scrambling over rocks in the dark, so we decided upon a high route, handrailing the upper cliffs. This worked pretty well. In the dark, we could perceive the cliff edge, changes in slope angle, reentrants and valleys. After two hours of careful night navigation, we arrived at the bothy.

Sunday morning, we ate well. I made some bread from scratch and we ate it with bacon, honey and butter. Our goal today was to reach Corpach Bay, about 8 thumbs away. The weather was due to be dry in the morning, then wet and very windy.

A little fearful of getting stuck again, we did a big chunk of the day journeying higher up, in the hills above the upper cliffs. This was enjoyable, with fine views. The rain held off thankfully, and after about six hours of trekking, we arrived at Corpach Bay. The place takes its name from the medieval practice of resting the dead on sea journeys to sacred burial places on Iona and Oronsay. From Islay, the boat crew and the deceased would come ashore at designated places. There was a resting place at Ruantallain on Jura to break up the journey to Oronsay, on Colonsay; and a cave at Corpach Bay, with an altar, was used as a resting place on the way to Iona. Somerled, mentioned above, sponsored a revival of the religious community on Iona, and I wonder whether he and his ancestors were behind this tradition.

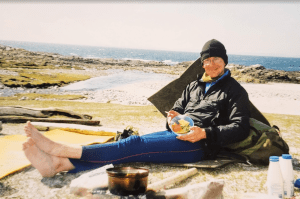

Corpach Bay is a beautiful place. All the ruggedness of the coastline to the north gives way to friendly sand dunes and machair. There is an abundance of great camping spots and plenty of streams for water. On an earlier trip, some friends and I were dropped off here by boat, and we spent three days camping, cooking on fires, climbing, swimming and exploring.

With the wind strengthening, we pushed on a little further and found a cave and sheltered camping spot. The cave would be great for cooking and hanging out in the evening. Having arrived with some daylight to spare, we collected lots of driftwood and set up our tarps.

Our fire in the cave was magnificent. As the rain poured down, we looked on warm and dry. We had a lovely time cooking and chatting til late. Iain cooked, making an excellent gnocchi, pesto dish, with cake and custard, and a few drams of Jura malt for afters. We also strung up a washing line and got all our socks dry. Wonderful.

Our goal on day three was to get to Cruib Bothy. A long day lay ahead, with the prospect of more night navigation. The day began with otter tracks, waterfalls and a visit to Julie Brook’s cave. Back in 1996, when Jim and I walked this coastline, I remember coming across a cabin built into the side of a dry arch. When I returned to Glasgow, I learned that this was the home and workplace of an artist called Julie Brook. Between 1991 and 1994, Julie lived in the arch and produced paintings and sculptures. Returning 29 years later, I was surprised to see that the main structure of the hut was still there. I’ve always been in awe of Julie’s resilience in living here.

Moving on from Julie’s cave, we passed through a section of the coastline with lots of raised beaches. Beyond that was Shian Bay (meaning fairy bay), a pleasant spot with a stony beach and machir. A few miles further on, we reached Ruantallain bothy. After a welcome rest, at 2 pm, we set off again with the aim of reaching Cruib bothy, about five miles away.

On our way to Cruib, I wanted to visit the King’s Cave (Uamh Righ). At first glance, the cave is no different from others. On closer inspection, however, limpet and oyster shells cover the floor of the cave, and you can see crosses on the walls. After my first visit to this cave in 1996, I did some research, reading about an archaeological dig of the site, conducted in 1978 by John Mercer.

Local legend links Robert the Bruce with the cave. The story goes that the king, in 1306, disheartened by defeats and seeking refuge in a cave, took inspiration from a spider repeatedly trying to spin its web. Competing locations for this cave are on Ratlin Island and the Isle of Arran. Interestingly, John Mercer’s excavation discovered a coin dating to 1322, too late, alas, for Robert the Bruce. John Mercer suggests the word ‘Righ’, meaning King in Gaelic, could have been misinterpreted for another archaic meaning: ‘to lay’. Like the caves at Corpach and Ruantallin, this cave could have been another resting place for the dead, where a corpse was stretched out on a bier. This could, he suggests, explain the crosses on the wall. Another explanation for the crosses comes from the archives of the Vatican. In 1560, Scotland became a resolutely Protestant country, and Catholicism was outlawed. In 1624, a clandestine mission by four Franciscan monks left Ireland for the Hebrides. One of the missionaries, Friar Patrick Hegarty, reached Jura and was said to have converted 102 souls. Perhaps this cave was the site of Patrick’s ministry!

John also found lots of evidence of the cave’s use, over millennia, as a temporary shelter to hunters, shepherds and fishermen. Microflints, an Iron Age Lignite arm ring, pottery, bone dice, bine pins and a plethora of animal remains were found: red deer, pig, sheep, fish, otter, seal, Greylag goose, Ptarmigan, sea-eagle, wolf and lots of shellfish.

With the daylight dwindling, we moved off again for Cruib. Iain took the lead and followed an argo-cat track, which helped us enormously. By 4 pm, it was dark and out came the head torches. The argo-cat track became hard to discern in the dark, and we relied more on navigating by landscape features. North east would take us downhill to a stream, then going east we’d reach the sea, handrail the sea for a bit, and over two ridgey peninsulas we’d reach the bothy. Straightforward enough, but the terrain was horrendous. As we descended to the stream, we encountered 1m high tussock grass, with swampy ground in between. It was really hard work. Our stream was a raging torrent as well, requiring lots of care. Step-by-step, however, we made slow progress, and at 6:30 pm we reached the bothy.

In the morning, we set off on the final part of our journey, the remaining 3 to 4 miles to the minor road and Iain’s car. We all really enjoyed the navigation, puzzling out all the folds in the landscape on our pathless route. In keeping with the best journeys, the end comes with some sadness. Penny and I looked on at the stretch of coastline, south of Loch Tarbet…. “Wouldn’t it be good to keep going? Another two or three days would do it”, I said. Our visit to Jura had been fantastic: amazing scenery, great companionship and a feeling of exploration and adventure.